- Home

- Andrew Cook

Ace of Spies

Ace of Spies Read online

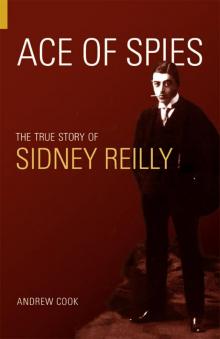

ACE OF SPIES

The True Story of

SIDNEY REILLY

ACE OF SPIES

The True Story of

SIDNEY REILLY

TO MY PARENTS

First published 2002

This edition first published 2004

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire,GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Andrew Cook, 2002, 2004

The right of Andrew Cook, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6953 9

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6954 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Introduction to the Second Edition

Preface

1 A Sudden Death

2 The Man From Nowhere

3 Gambit

4 The Broker

5 The Colonel’s Daughter

6 The Honey Pot

7 Confidence Men

8 Code Name ST1

9 The Reilly Plot

10 For Distinguished Service

11 Final Curtain

12 A Change of Bait

13 Prisoner 73

14 A Lonely Place to Die

Appendices

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Notes

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andrew Cook worked for many years as a foreign affairs and defence specialist, and was aide to George Robertson (former Secretary of State for Defence, now Lord Robertson of Port Ellen and Secretary General of NATO) and John Spellar (former Minister of State for the Armed Forces). The contacts he made enabled the author to navigate and gain access to classified intel-ligence services archives. During his ten years researching this book, he was only the fifth historian to be given special permission, under the 1992 ‘Waldegrave Initiative’ by the Cabinet Office, to examine closed MI6 documents that will never be released, documents not seen by any previous biographer of Reilly. Since working directly as a foreign affairs and defence specialist, Andrew Cook has worked as a professional historian in colleges and universities. He is a regular contributor on espionage history to The Guardian, The Times and BBC History Magazine and has appeared on national radio and television. His next book, M: MI5’s First Spymaster, will be published by Tempus. The author’s Sidney Reilly website is www.sidneyreilly.com. He lives in Bedfordshire.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Iowe a debt of gratitude to all those involved in the development of this book. It took many years to research and a large number of people were involved in the project from inception to completion.

My particular thanks go to the principal researchers who assisted me: Jordan Auslander (USA); Dmitry Belanovsky (Russia); Vladislav Kiriya (Ukraine); Dr Sylvia Moehle (Germany); and Stephen Parker and Graham Salt (UK). I would also like to thank Michel Ameuw (France), Dr Michael Attias (UK), Marc Bernstein (USA), Norman Crowder (Canada), Alex Denisenko (Poland), Lynda Fagan (UK), Dr Tatiana Filimonova (Russia), Sigita Gasparaviciene (Lithuania), Maria Herman (Brazil), Geoffrey Hewlett (UK), Reinhard Hofer (Austria), Sinan Kuneralp (Turkey), Sean Malloy (USA), Mary Morrigan (Eire), Irina Mulina (Russia), Danna Paz Prins (Israel), Mikhail Sachek (Belarus), Ishizu Tomoyuki (Japan) and Mark Windover (USA) for additional assistance with research.

In the pursuit of source material, I am much indebted to ministers and former ministers for whom I have previously worked, for their advice concerning access to UK records. As a result of an approach to the Cabinet Office, the government agreed to provide me with a briefing based on the records of Sidney Reilly’s service with the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), for the purpose of this book. This has helped enormously, as indeed has the opportunity to compare UK records with those of the Federal Security Service (FSB) in Russia and the US Bureau of Investigation (the forerunner of the FBI) in Washington DC.

The help and co-operation of the families of those who played a role in Reilly’s story has been greatly appreciated, as has the assistance of Francis & Francis (private investigators), who helped in tracing them. Special gratitude is owed to Diane Briscoe, George Burton, Carmel Callaghan-Sinnott, Teodor Gladkov, Boris Gudz, Edward Harding-Newman, Charles Lewis, Gustav Nobel, Trevor Melville, Anne Thomas, Viscount Thurso and Brigid Utley.

I have been most grateful to those who have previously written on this and related subjects for speaking or corresponding with me – Gill Bennett, Gordon Brook-Shepherd, Alan Judd, the late Michael Kettle, Margot King, Robin Bruce Lockhart, Professor Ian Nish, Gail Owen, Professor Richard Spence, Carol Spero and Oleg Tsarev.

A special thank you to Lisa Adamson, Laura Ager, Caroline Beach, Daksha Chauhan, Alison Cook, Julia Edwards, Elaine Enstone, Janet Jacobs, Bob Sheth, Selina Short and Chris Williamson for their hard work at various stages of this project. Also to Eurotech Ltd for their sterling work in translating the masses of source material from Russian, German and French into English.

There are equally a number of individuals I would like to thank for their help, but cannot name for reasons of protocol. However, they are already aware of my gratitude and have been thanked in person. Last, but certainly not least, my thanks go to my editor Joanna Lincoln and to my publisher Jonathan Reeve for his support, enthusiasm and advice throughout.

INTRODUCTION TO THE

SECOND EDITION

When the first edition of this book was published in October 2002, it received a great deal of media coverage, not only in Britain but around the world. Since then, the first edition has been reprinted in this country and translated into several foreign editions. When the idea of writing a revised and updated second edition was suggested by my publisher Jonathan Reeve, I saw it as an ideal opportunity to follow up several further lines of enquiry that were still outstanding at the time of submitting the manuscript for the first edition. As a result, a wealth of new evidence has been uncovered that sheds new light on significant episodes in Reilly’s life.

For example, photo-forensic work by Ken Linge, which was still being undertaken at the time the first edition was being printed, is now concluded and has made a major contribution to establishing Reilly’s parentage and family lineage. Another mystery concerning his involvement in a crime that forced him to flee from France to England in 1895 is also solved thanks to new research in France by Michel Ameuw. Other new discoveries include German files on Reilly’s shady commercial dealings in the Ottoman Empire before the First World War, letters he wrote in 1917 which clear up the mystery of his whereabouts in the autumn of that year, and the discovery of a repository of papers belonging to Major J.D. Scale, the intelligence officer who recruited Reilly to the Secret Intelligence Service (better known today as MI6) in 1918.

In Moscow, new finds include the personal testimonies of Reilly’s mistresses Olga Starzhevskaya and Elizaveta Otten, written during their captivity in Butyrka Prison. These previously unpublished accounts not only provide a glimpse of their pers

onal relationships with Reilly but give a unique insight into the secret life he was living in Russia during the spring and summer of 1918. Perhaps the most astonishing new account, however, is that of Boris Gudz, a former OGPU officer who took part in the 1925 ‘Trust’ operation that resulted in Reilly’s arrest and execution. Gudz, who celebrated his 100th birthday shortly before I met him in Moscow in August 2003, was able to provide first-hand recollections that were invaluable in piecing together the last few weeks of Reilly’s life.

Taken together, these and other new sources, many of which are published in this book for the first time, make a unique contribution to this definitive work of reference on the life of the Ace of Spies, Sidney Reilly.

The idea of writing a spy novel had apparently been in Ian Fleming’s mind for a decade before he finally decided to commit the book to paper. Little did he know the phenomenon he was about to create when he sat down behind his typewriter on the morning of 15 January 1952 to start the first chapter of Casino Royale. Working at ‘Goldeneye’, his Jamaican holiday home, he completed the 62,000-word manuscript in a little over two months.1 On the shelf in his study was the book that had gifted him the name of his hero, Field Guide to Birds of the West Indies, by the ornithologist James Bond.2 Not long after its publication in April 1953, Fleming told a contemporary at the Sunday Times, where he worked as foreign manager, that he had created James Bond as the result of reading about the exploits of the British secret agent Sidney Reilly in the archives of the British Intelligence Services during the Second World War.3

PREFACE

As personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, Cmdr Ian Fleming was a desk-bound intelligence officer who liaised closely with other agencies involved in the clandestine world of espionage. He learnt a great deal about the operational history of his own department, including its role in the greatest intelligence coup of the First World War – the cracking of the German diplomatic code 0070, which gave Fleming the inspiration for Bond’s own code number 007.4 This background knowledge enabled him to draw on a rich seam of characters, experiences and situations that would prove invaluable in creating the fictional world of James Bond.

One of Fleming’s wartime contacts, for example, was Charles Fraser-Smith, a seemingly obscure official at the Ministry of Supply. In reality, Fraser-Smith provided the intelligence services with a range of fascinating and ingenious gadgets such as compasses hidden inside golf balls and shoelaces that concealed saw blades.5 He was the inspiration for Fleming’s Major Boothroyd, better known as ‘Q’ in the Bond novels and films.

Having a fascination for gadgets, deception and intrigue, Fleming was particularly attracted to the ‘black propaganda’ work undertaken by the Political Warfare Executive, headed by former diplomat and journalist Robert Bruce Lockhart, with whom he also struck up an acquaintance.6 In 1918 Lockhart had worked with Sidney Reilly in Russia, where they became embroiled in a plot to overthrow Lenin’s fledgling government. Within five years of his disappearance in Soviet Russia in 1925, the press had turned Reilly into a household name, dubbing him a ‘Master Spy’ and crediting him with a string of fantastic espionage exploits.

Fleming had therefore long been aware of Reilly’s mythical reputation and no doubt listened in awe to the recollections of a man who had not only known Reilly personally but was actually with him during the turmoil and aftermath of the Russian Revolution. Lockhart had himself played a key role in creating the Reilly myth in 1931 by helping Reilly’s wife Pepita publish a book purporting to recount her husband’s adventures.7 As a journalist at the time, Lockhart also had a hand in the deal that led to the serialisation of Reilly’s ‘Master Spy’ adventures in the London Evening Standard.

Although Reilly was a spark or catalyst for Fleming’s ‘Master Spy’ concept, Bond’s personality was a fictional cocktail, culled from a range of characters, including Fleming’s own.8 There are certainly threads of Reilly’s hard-edged personality to be found in the Bond who inhabits the pages of Fleming’s books. The literary Bond was visibly a much darker, more calculating and altogether more sinister character than his big screen counterpart, who has tended to dilute Fleming’s original concept over the years.

Like Fleming’s fictional creation, Reilly was multi-lingual with a fascination with the Far East, fond of fine living and a compulsive gambler. He also exercised a Bond-like fascination for women, his many love affairs standing comparison with the amorous adventures of 007. Unlike James Bond, though, Sidney Reilly was by no stretch of the imagination a conventionally handsome man. His appeal lay more in the elusive qualities of charm and charisma. He was, however, equally capable of being cold and menacing. In many ways, the closest modern fictional character to resemble Reilly is Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone in The Godfather, a man of controlled coldness and deadpan cal-culation. Like Corleone, the equally calculating Reilly had a powerful hold over women — or, at least, a particular kind of woman — which he never failed to exploit.

But who was Sidney Reilly and what were the forces that drove him? To lovers, friends and enemies alike, Reilly remained a mystery. In spite of the many books that have been written about him, often themselves making contrary claims, major questions still remain unanswered about his true identity, place of birth and the precise facts surrounding his disappearance and death. During his life Reilly laid an almost impenetrable fog of mystery and deception around his origins as he adopted and shed one identity after another. Those who entered this ruthlessly compartmentalised life knew only what Reilly himself had told them.

Over a century of falsehood and fantasy, both deliberate and intentional, has obscured the real Sidney Reilly. Reilly’s tendency to be something of a Walter Mitty character, telling tall tales of great espionage feats, has only added to the legend and muddied the water still further. To piece together an accurate picture of his extraordinary life it has been necessary to shed all preconceptions and to return to square one, starting from scratch in gathering together as many primary sources as possible.

The ability to draw on many classified, restricted and hitherto unpublished sources in Britain, Canada, Germany, Japan, Poland, Ukraine and the United States has helped this task immeasurably. The descendants of a number of those who played key roles in Reilly’s story have also been tracked down and interviewed. Their help in particular has provided many of the missing pieces in the jigsaw of his life, and revealed for the first time how he was propelled at the age of only twenty-five into the life of an international adventurer.

ONE

A SUDDEN DEATH

Of Newhaven there is little to say, except that in rough weather the traveller from France is very glad to reach it, and on a fine day the traveller from England is happy to leave it behind.1

These rather unflattering words were written by the travel writer E.V. Lucas in 1904. However, it is often in unremarkable places such as this that some of the most remarkable things happen. Indeed, some six years before Lucas wrote these words, Newhaven’s London & Paris Hotel was the unwitting host to an event that was to have far reaching repercussions, not only for a twenty-four-year-old heiress, but also for a man who was to become the epitome of the twentieth-century spy.

Incorporated into the design of Newhaven Harbour Station, the imposing three-storey stucco building was luxuriously furnished with thirty bedrooms and was everything the discerning Victorian traveller could possibly want or expect. It was here, at the quayside platform on the afternoon of Friday 11 March 1898, that a sixty-three-year-old invalid was helped down from the train into his wheelchair. Accompanied by his nurse, Anna Gibson, the Reverend Hugh Thomas2 proceeded to the reception desk to announce his arrival. He and the nurse had booked two rooms up to and including Monday 14 March, when his twenty-four-year-old wife, Margaret, was due to arrive from London. The three would then take the 11.30 a.m. boat train to Paris en route to a holiday in Egypt.

Despite the trappings of her social status, Margaret may well hav

e felt that a part of her life was somehow empty. It was almost certainly her need for attention and affection that ultimately led her to respond to the overtures of Sigmund Rosenblum, of the Ozone Preparations Company.3

Hugh Thomas and Sigmund Rosenblum first met in 1897. Thomas, a sufferer from Bright’s Disease, a chronic inflammation of the kidneys, was one of many who succumbed to the siren voice of the patent medicines popular at the time, peddled by companies such as Ozone Preparations Company as offering miracle cures. These companies’ claims were greater than those of conventional medicine, who only prescribed bed rest, a low protein diet, massive doses of Jalap, and blood letting – the attraction of patent medicines to sufferers such as Thomas was obvious.

Hugh Thomas and Sigmund Rosenblum met regularly throughout 1897 at the Manor House, Kingsbury, and at 6 Upper Westbourne Terrace, London. Indeed, it was at the Manor House, in the summer of 1897, that Thomas introduced Rosenblum to Margaret.4 It has been claimed that the Thomases first met Sigmund Rosenblum in Russia, during a tour of Europe they undertook in 1897.5 It has been claimed, too, that Margaret’s relationship with Rosenblum developed as he accompanied them from hotel to hotel on a melodramatic journey back to England.6 The facts, however, tell a very different story. Although a passport was not as necessary as it is today for foreign travel, to enter Russia, Hugh and Margaret Thomas would most certainly have required one. British passport records show, however, that the Thomases never at any time applied for, or were ever granted, passports for Russia.7 Furthermore, Thomas household records make no reference to any foreign trips or holidays undertaken in 1897, although in December of that year, plans were made for a holiday in Egypt the following March.

Whose idea this Egyptian holiday was we do not know. Whether these plans were made with a straightforward holiday in mind or something a good deal more sinister is very much dependent upon one’s interpretation of the evidence.8 What we do know, however, is that the planning, arrangements and bookings were made by Margaret, as Thomas Cook records show. Shortly before their departure, Margaret arranged an appointment for her husband and herself to visit a local solicitor. On Friday 4 March they made their way to 13 St Mary’s Square, Paddington, a short distance from their home. Before a clerk, Hugh Thomas appointed the Thomas family solicitor, Henry Lloyd Carter, and Margaret as his Executors. The Will itself declared the following:

M

M Ace of Spies

Ace of Spies The Great Train Robbery

The Great Train Robbery The Ian Fleming Miscellany

The Ian Fleming Miscellany